Unforgettable Officer - LTC Vernon McGuiire

1352, 28 Mar 2015

World War II POW ***** Finance Corp Officer

My Most Memorable Finance Corps Officer

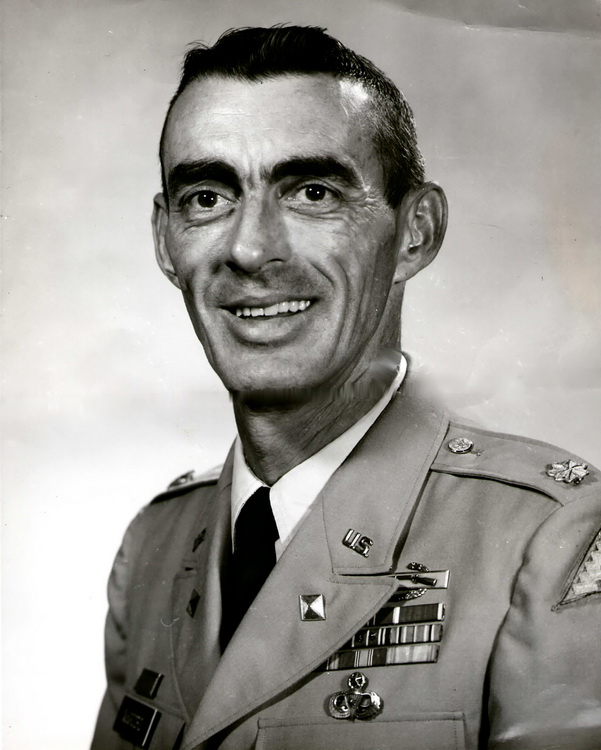

In early March 1968 I reported to the Finance Officer for the 101St Airborne Division in Viet Nam. The officer sitting behind the desk was a Lieutenant Colonel. He had a full head of salt and pepper hair. His face had a dark tan; and, it was weathered and craggy looking. Having only recently completed Airborne School, I could not help but to notice that he wore the wings of a Master Parachutist with a Gold Star, indicating he had made a combat jump.

When I entered his office, he immediately stood and started around his desk toward me with his right hand extended. He was sort of a wiry and thin man whom I estimated to be between five foot ten and six feet. He stood erect, possessing the most military bearing of any officer I had seen since I left Infantry OCS. I had branch transferred from the Infantry to the Finance Corps. At that time, I would have estimated his age to be in the mid to late fifties. He was in fact forty-seven.

A large smile came across his weathered face; and, there was a sparkle in his eyes. His reaction caused me to feel as though he had been waiting especially for me to arrive.

As I reached to grasp his extended hand I noted his hand had a slight tremble. But mostly, I notice the distortion and slight disfigurement in tips of his fingers. Some of his fingers appeared to be missing finger nails. When he grasped my right hand, his left hand came over the top of both our hands which steadied our hand shake. It was then I noticed the fingers on his left hand were similar to the ones on his right hand.

Looking me directly in the eyes and, saying before I could speak, “Welcome aboard, Lieutenant Daniels, I am Lieutenant Colonel Vernon McGuire.”

I did not spend any more than about thirty minutes with Colonel McGuire that day because I was on my way to Phan Rang to replace, newly promoted, Major Walt Labovich, the 1St Brigade Finance Officer who was rotating back to the States. During our brief meeting Colonel McGuire informed me that within the next two months I would be moving the Brigade Finance Office from Phan Rang to Bien Hoa where it would be merged with the Division Finance Office.

True to his word, I was back in Bien Hoa within the next forty-five days. I worked with Colonel McGuire, practically on a daily basis, for the next nine months. I also had the privilege and honor of working for him another six months when he was the Finance School Secretary and I was his Assistant School Secretary. The following story is one of a remarkable leader; and, one that I believe should be remembered. Most of the story was related to me personally by Colonel McGuire as our friendship developed over a combined period of two years.

---00000---

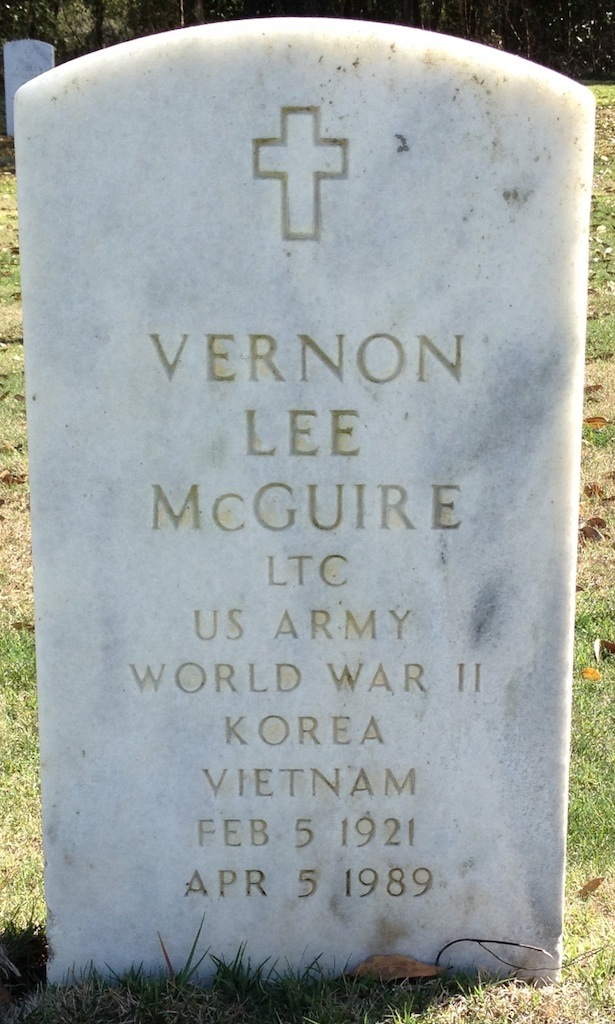

Lieutenant Colonel Vernon Lee McGuire was born on February 5, 1921 in Ottumwa, Iowa. Ottumwa is approximately twenty-eight miles north of the Missouri state line and seventy-three miles west of the Illinois state line.

Lieutenant Colonel Vernon Lee McGuire was born on February 5, 1921 in Ottumwa, Iowa. Ottumwa is approximately twenty-eight miles north of the Missouri state line and seventy-three miles west of the Illinois state line.

Vernon McGuire enlisted in the Army in San Francisco, CA on 2 October 1942, volunteered for parachutist duty and was assigned to Company C, 508th PIR which was just forming at camp Blanding, FL.

On December 6, 1944, D Day, Sergeant (E5) Vernon McGuire exited a C-47 aircraft at what he thought to be the designated jump altitude of 600 feet. History now reveals that many of the aircraft released the jumpers at an altitude of 300 feet or less; and, at speeds much greater than the jumpers were accustom to jumping.

Sergeant McGuire’s designated drop zone was approximately a quarter of a mile southwest of the village Ste. Mere. Eglise. The assembly point was a railroad track located further inland from the drop zone.

As was the case with so many other jumpers during that dramatic night jump, Sergeant McGuire’s aircraft failed to properly identify the drop zone and his stick came down in a forest. He described his descent as a frightful experience because the tracer fire seemed to be coming directly at him; and there were lots of muzzle flashes below him. He felt fortunate that he had avoided a tree landing because there were trees all around him.

Shortly after landing, he linked up with another 82nd trooper and the two of them started making their way in the direction they believe to be the assembly point. Luck did not smile on the two lost 82nd troopers because just before day break, still without having located the railroad track, they were confronted with the word “Halt”, rendered in a heavy German accent.

The two unlucky troopers, now prisoners of war, were marched at gun point, to a nearby waiting half track. As they loaded into to back of the truck they discovered about a dozen other 82nd troopers already sitting in the bed of the truck. One appeared to have either a broken arm or shoulder; and, was in considerable pain.

Once they were loaded, the truck pulled out. After short ride; and, in Colonel McGuire’s words, “We wondered around half the night and, after ten minutes, crossed that son-of-a-bitch railroad track”. As a side note, up until Colonel McGuire retired, one of his favorite expressions, when he got upset, was still “Son-of-a-bitch”.

After about an hour of heading in an easterly direction the truck came to a stop at a railroad siding. On the siding were six to eight box cars; or, cattle cars if you were from Iowa. A number of the cars had their doors closed; but, there appeared to be people inside.

Once the troopers had off loaded from the truck they were lined up and relieved of all their personal items such as wallets, watches, money, pictures and dog tags. All military items were also taken from them before they ever loaded on the truck. They were then herded toward one of the cattle cars where the door was closed.

When the door to the cattle car was opened they were told to get inside. Soldiers inside the car reached down to give them a lift up.

Inside the car were at least fifty soldiers. Some were sitting; but, most were standing. In one corner of the car was a rusty fifty gallon barrel that had been cut in half. The barrel, which served as the toilet, was almost full.

For the next four days the box cars set on the siding. The number inside grew to over capacity. Unfortunately, the toilet facility remained the same size; and, by now soldiers were beginning to experience cases of diarrhea. The barrel was emptied only once a day by some of those inside the car. Needless to say, overflow of the contents was a common occurrence.

The first couple of days the prisoners were only given water twice a day. There was no food. Finally, on the third day a few loafs of bread were thrown inside the car. Colonel McGuire said the first time food was thrown in, the scene was like a pack of ravishing dogs. It was then they elected the two largest guys in the car to ration the food when it was provided.

During the next four days they heard periodic rifle fire. Word would quickly spread between cars there had been an escape attempt and those attempting to escape were shot. On the fourth day a train came by the siding pulling several other box cars. The cars that were on the siding were added to the train and they started to move, again moving northeastward.

As the train rumbled northeastward across France and Germany the men on board thought they were never going to reach their destination. The train stopped once or twice a day for the toilet to be emptied; and, to provide some meager food to the prisoners, consisting primarily of what was alleged to be, watered-down cabbage or potato soup and a crust of bread. Colonel McGuire said he never saw any cabbage leaves or potatoes in the soup.

As the train rumbled northeastward across France and Germany the men on board thought they were never going to reach their destination. The train stopped once or twice a day for the toilet to be emptied; and, to provide some meager food to the prisoners, consisting primarily of what was alleged to be, watered-down cabbage or potato soup and a crust of bread. Colonel McGuire said he never saw any cabbage leaves or potatoes in the soup.

There were times when the box cars would be parked on a rail siding from a few hours to a couple of days. At each stop they would hear rifle fire. Rumors were that prisoners were routinely being taken off the train and shot; or, there had been another escape attempt. Colonel McGuire estimated it took two weeks for the train to reach the prisoners’ destination.

Thus, began his life at Stalag IIIC Alt Drewitz Brandenburg, Prussia.

Colonel McGuire said that when he finally got out of that cattle car, the camp was a welcomed site. He had been closed up in the car for almost three weeks; and, the filth and stench was unbearable. The stench from the camp was almost like fresh air.

He was assigned to a barrack that was already about ninety per cent of capacity. For new guys, the reception in barrack was not always a warm one. First, he was viewed suspiciously by the “old timers”; and, secondly, he was adding to an already cramped situation. There was great concern among the residents that a new guy might be a plant by the Germans. Colonel McGuire said one quickly learned not to ask questions that might suggest one was trying to acquire information about plans for escape.

Over the next couple of months Sergeant McGuire was interrogated several times by camp officials. The two things that surprised him most about his interrogations sessions were first, how articulate and fluent the camp commander was in English. And, secondly, how much the camp commander already knew about him. For example, the commander knew his Division; Regiment; his commanding officer; his martial status; and, that he was from Iowa. Colonel McGuire’s exact words were, “I don’t know where that son-of-a-bitch got that information.”

After approximately six months in the camp Sergeant McGuire learned that an escape plan was in the works. That was when he was recruited to be a member of the diversion team. The members of the escape team had been decided months before his arrival in the camp. It was also during the winter of 1944 that his fingers experience frost bite. However, the camp did not have the medical supplies to treat frost bite. He again commented, “I know my fingers look like a son-of-a-bitch; but, at least I have all of them!”

In May of 1945, just before day break, Sergeant McGuire awoke to an eerie quiet in the camp. He said when he and some of the other guys walked outside their barrack; it appeared that the entire cadre had vanished. There were no guards in the towers; nor, any movement around the camp commander’s headquarters. The gate remained locked.

All suspected something sinister by the Germans, so there was no movement made toward the gate. Rumor for sometime had been the Germans were being defeated; and, most of the prisoners thought if that were the case, all the prisoners would be executed before the Germans left the prison. So the prisoners stood in the yard; leaned against a barrack; or, just sit down on the ground.

Shortly after day break on 2 May 1945, vehicle movement and the sound of boots striking the dirt road could be heard in the distance. The sounds were getting closer to the camp. Sergeant McGuire said he thought the Germans were returning, possibly to execute the prisoners.

But, to the surprise of the prisoners, the advancing soldiers were Russians. Within a matter of minutes several Russian soldiers cut the locks off the gate and swung the gate open. A Russian officer entered the gate; and, in broken English, announced they were free to go home. The officer turned and rejoined the Russian Army as it continued its advance down the road.

Again, in Colonel McGuire’s words, “Those Russian sons-of-bitches didn’t offer us any help. They didn’t even tell us which way to go.”

After savaging a few eatable items from the prison kitchen, Sergeant McGuire paired up with another soldier and the two started walking west. When they passed through the first village they stole a bicycle. They then took turns with one pedaling and the other riding on the handle bars. Their greatest obstacle was the Russian check points.

Periodically, the two Americans were stopped by Russians and interrogated. During one interrogation session they learned the Russians had great respect for American aviators; so, they began to claim to be American aviators.

After about the fourth time they were stopped Sergeant McGuire convinced the Russians to give them a written pass to expedite them through future check points. Unfortunately, when they were stopped two check points later, they were stopped by “a Russian son-of-a-bitch who could not read; and, he tore up their pass.”

For the next four weeks Sergeant McGuire and his friend trekked west across Germany toward U.S. forces, stealing and begging for food and for transportation as they went. Colonel McGuire said it was late May 1945 before they finally made contact with U.S forces. A month later, former POW McGuire was back in the United States.

Of course that is not the end of Colonel McGuire’s story. Colonel McGuire obtained his commission in the Infantry. And, while I think he was more comfortable in the Infantry, his wife, Lois[1], convinced him he needed to acquire some skills he could apply once he retired. And, it was for that reason, he branch transferred to the Finance Corps.

The first time I ever saw Colonel McGuire show his disappointment with the Army was in the summer of 1968 when the 101st was re-designated, for a short period of time, from “Airborne” to “Airmobile”. A summarized version of his barrage of comments would be, “Don’t those sons-of –bitches in Washington know anything about the history of the 101st Airborne Division. Someone needs to tell them to get their heads out of their asses and do the right thing!” Apparently someone did because the division signage was changed from “Airmobile” back to “Airborne”.

Lieutenant Colonel McGuire departed the 101st Airborne Division in December 1968 for assignment with the U.S Army Finance School where his duties were that of School Secretary.

I departed the 101St in February 1969 for the Army Finance School. Approximately four months later Lieutenant Colonel McGuire asked me to be his Assistant. I soon discovered that he took a personal interest in any soldier being assigned to either the 82nd or 101st. He made the time to counsel each one. Depending upon the division to which the soldier was being assigned, he made the point to wear his blouse that proudly displayed either the 82nd Airborne patch or the 101st Airborne patch, both of which he earned during combat tours.

The second time I saw sadness in the old Airborne Trooper’s eyes was the day he faced mandatory retirement. He was a reserve officer and therefore was required to retire at twenty years of commissioned service. With his enlisted time, he had given over thirty years to the U.S. Army. When asked to make some remarks at his retirement ceremony, his only statement was to drop to the floor of the School Commandant’s office and knock out a perfectly executed pushup for each year of his military service. He then bounced to his feet and shouted, “Airborne all the way, Sir!”

The second time I saw sadness in the old Airborne Trooper’s eyes was the day he faced mandatory retirement. He was a reserve officer and therefore was required to retire at twenty years of commissioned service. With his enlisted time, he had given over thirty years to the U.S. Army. When asked to make some remarks at his retirement ceremony, his only statement was to drop to the floor of the School Commandant’s office and knock out a perfectly executed pushup for each year of his military service. He then bounced to his feet and shouted, “Airborne all the way, Sir!”

I never saw Lieutenant Colonel McGuire again after that day; but, he was the most memorable Finance Corps Officer I ever knew. He personified the professional soldier and inspired others through his leadership attributes and his genuine love for our Army.

He died April 5, 1989 at the age of 68 in Jacksonville, Florida. He was buried in Florida National Cemetery. I suspect he may have been one of a very small number of POWs to serve in the Army Finance Corps.

Earl Daniels

Colonel, U.S. Army Finance Corps (Retired)

[1] Lois H McGuire was born on 09/06/1922 and died on 06/29/2002 at the age of 79. Lois McGuire is buried in the cemetery: Florida National Cemetery, which is located in Bushnell, FL.

(if you wish to post a comment on this bulletin, please log in)